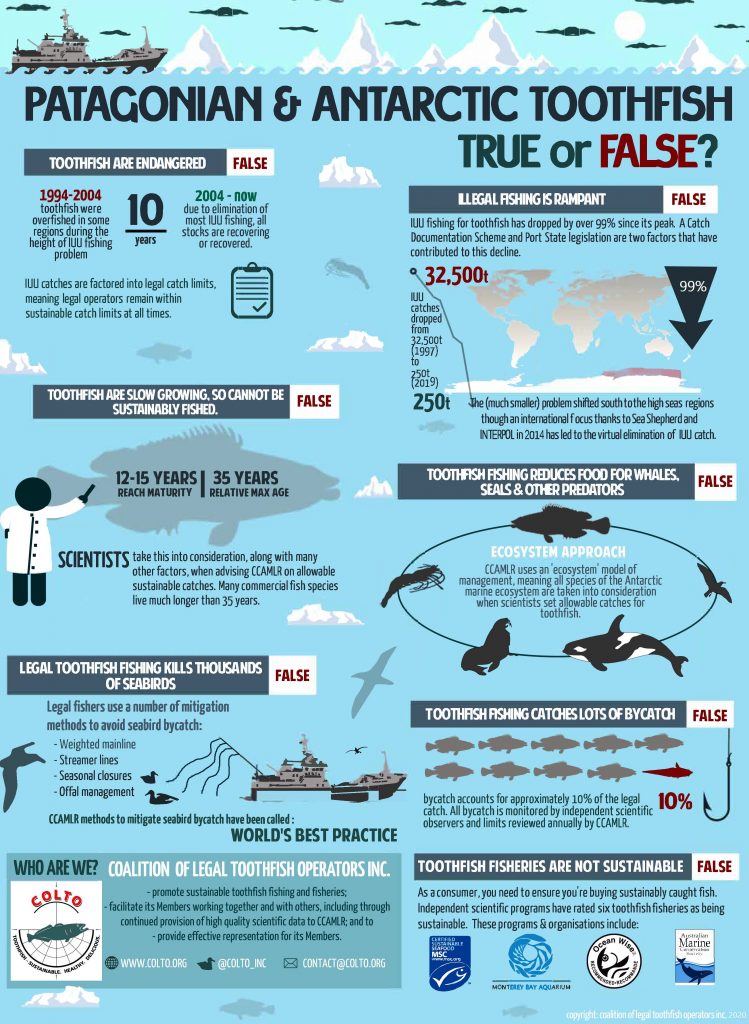

Statement 1. Toothfish are endangered.

Toothfish are not endangered and never have been.

In a number of regions, stocks were significantly overfished as a result of illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing during the period from 1996 – 2005 in particular. All of those stocks are now either in recovery, or have recovered, following positive actions by many at eliminating IUU fishing, and restraining legal allowable catches to sustainable levels. Estimates of IUU catches have reduced from a peak of over 30,000 tonnes in 1997 to an average of less than 250 tonnes per annum between 2016-2020. All estimates of IUU catches are included in scientific stock assessments made for stocks of toothfish, to ensure they’re taken into account when assessing the sustainability of any level of legal catches.

For more information, see our IUU History and IUU Fact Sheet pages.

Statement 2. Illegal fishing is rampant in toothfish fisheries.

This has not been correct for over 15 years.

In the mid to late 1990s and early 2000s there were over 55 IUU vessels fishing illegally for toothfish in the Southern Oceans. Since this time, largely through the success of CCAMLR, national governments, legal industry and conservation NGOs, IUU fishing for toothfish is the lowest it has ever been, with a current estimate of near zero. Measures taken to eliminate IUU fishing included the introduction of satellite monitoring systems on all legal boats; catch documentation systems to track all legal product; certification and traceability schemes to ensure only legal products entered the main markets; compliance and surveillance activities by national governments and international agencies (such as INTERPOL); and many other measures.

In this time, IUU fishing for Patagonian toothfish dropped by 99% as illegal operators were been pushed out of countries’ Exclusive Economic Zones and further south on to the high seas, where they then targeted Antarctic toothfish with gillnets.

Unfortunately, due to the international law of the sea, this type of fishing on the high seas without a license from a responsible CCAMLR member nation is not necessarily illegal; but is definitely unregulated and unreported. Unscrupulous operators had been using the legal ‘loophole’ to avoid sanctions in more recent years, although the advent of INTERPOL pressure, the high profile Operation Icefish by Sea Shepherd in 2015, and the ongoing collaborative actions by governments globally has seen this loophole rapidly disappearing for toothfish IUU operators.

For more information, see our IUU History and IUU Fact Sheet pages.

Statement 3. Toothfish are slow growing, long lived and so can’t be sustainably fished.

This is false.

A good measure of the maximum age of a fish species is the age by which 99% of the population has died. This is called relative maximum age. The relative maximum age for both Antarctic and Patagonian toothfish is around 35 years, compared with snapper 60 years and hapuku (groper) 46 years. Toothfish grow nearly 30 cm in the first two years of life, and to around 65 cm in the first five years. They typically grow to over 1m in their first 10 years of life.

From the figure it is apparent that in terms of longevity, Toothfish lie very much in the middle of the range – close in fact to blue cod to which they are distantly related. They are not long-lived in comparison to many other temperate species.

Toothfish can be sustainably fished, as long as the scientists take into account the relatively slow growth, and longer life span of the fish when they are calculating the allowable sustainable catches in the stock assessment model. All of these factors are taken into account, along with many other biological details which are derived from either independent scientific surveys, or fishery-dependent data (e.g. tag and release programs, implemented by government scientific observers, and monitored and assessed by national and CCAMLR scientists). As mentioned earlier, scientists from both national governments, as well as CCAMLR, also take into account any estimated IUU catches of toothfish from each separate stock, so that sustainable legal catches will remain sustainable. That means that any IUU catches will reduce the available legal catch, as scientists will deduct those IUU catches from any possible legal fishing, before setting annual allowable catches.

For more information, please see the CCAMLR scientific report pages, and our Toothfish fact sheets for specific fisheries.

Statement 4. Legal toothfish fishing kills thousands of seabirds

This is not true.

Toothfish fisheries used to catch a lot of seabirds, until the late 1990s when legal industry operators joined with fishing gear manufacturers, ornithologists, CCAMLR member scientists, and seabird conservation groups to develop seabird mitigation measures in toothfish fisheries. The result was a series of measures designed to avoid the capture of seabirds that is now used internationally in fisheries to demonstrate “World’s best practice”.

Measures used include streamer lines when setting hooks (to avoid birds grabbing the hooks), integrated weight mainlines which sink rapidly once in the water (again to avoid birds grabbing the hooks); season restrictions to only operate during periods of low seabird abundance; no offal overboard during periods of fishing (or, in some instances, no offal overboard at any time) to avoid attracting seabirds to the boats; and many other measures. This is all monitored by the international scientific observers, carried on board every legal vessel, during every fishing trip made for toothfish.

In 2013, the Chair of the CCAMLR Scientific Committee stated that seabird bycatch in CCAMLR fisheries were at ‘near-zero’ levels. This compares to estimates of IUU catches of seabirds of up to 140,000 in a single year alone in 1998 and 2002 as they used no seabird mitigation measures when fishing illegally.

For more information please see our Seabirds page.

Statement 5. Toothfish fishing catches lots of bycatch

This is not true.

Toothfish fishing actually has very low bycatch levels – generally in excess of 90% of the fish caught are toothfish, and some of the bycatch species – particularly skates – are able to be tagged and released, or released alive. All of the toothfish catches, and bycatch, are recorded by both the operators and the independent scientific observer(s) carried on every legal boat, for every fishing trip. The statistics are all provided to CCAMLR, and can be found in the CCAMLR Statistical bulletin by area, by species, by flag state and many other details such as fishing effort and so forth.

Statement 6. Toothfish fishing reduces the amount of food available for some whales, seals and other large predators

This is not true.

All sustainable allowable catches set for toothfish specifically allow for at least 50% of toothfish populations to avoid being fished. This 50% limit is projected for 35 years and is calculated each new assessment, generally every 2 years. This is designed both to ensure the stocks of toothfish can remain sustainable, but also to take into account the need to leave ‘additional’ toothfish in the ecosystem to provide adequate food for higher order predators such as toothed whales, sea lions and so forth. There are specific monitoring programs in place to detect changes to the ecosystem and food web.

The CCAMLR decision rules for scientific setting of allowable catches explicitly identify this need to provide for the ecosystem impacts of fishing.

Statement 7. Toothfish fisheries are not sustainable

This is not true.

Toothfish fisheries have gone through an extraordinary change in a relatively short amount of time. From the commercial toothfish fisheries being discovered and governed by CCAMLR in the early 1990s, then the influx of IUU fishing in the late 1990s until the mid-2000s, to the then recovery phase of the mid-to-late 2000s once IUU fishing had been eliminated from within national EEZs.

The scientists from 25 member nations of CCAMLR oversee all assessments of toothfish fisheries, and scientific observers oversee all the legal fishing activities and information gathering at sea. This information is used to help better understand toothfish stocks, as well as to monitor the health of those stocks over time, to ensure they remain sustainable.

Those toothfish fisheries which were particularly badly impacted by IUU fishing, are still in a ‘recovery’ phase, with allowable catches that are set deliberately low to help facilitate recovery of those stocks, while at the same time being able to collect data on the stock to be able to assess it. In addition, other fisheries have recovered mostly, or fully, from the IUU activities and are now independently recognised and verified as sustainable.

Since 2004, seven toothfish fisheries, totalling over 50% the world’s toothfish catch have been independently certified as sustainable and well managed by the Marine Stewardship Council. More information on those fisheries can be found on the MSC website. Other independent scientific programs have also reviewed and rated toothfish fisheries as sustainable, including the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch program; AMCS; OceanWise, plus many others.